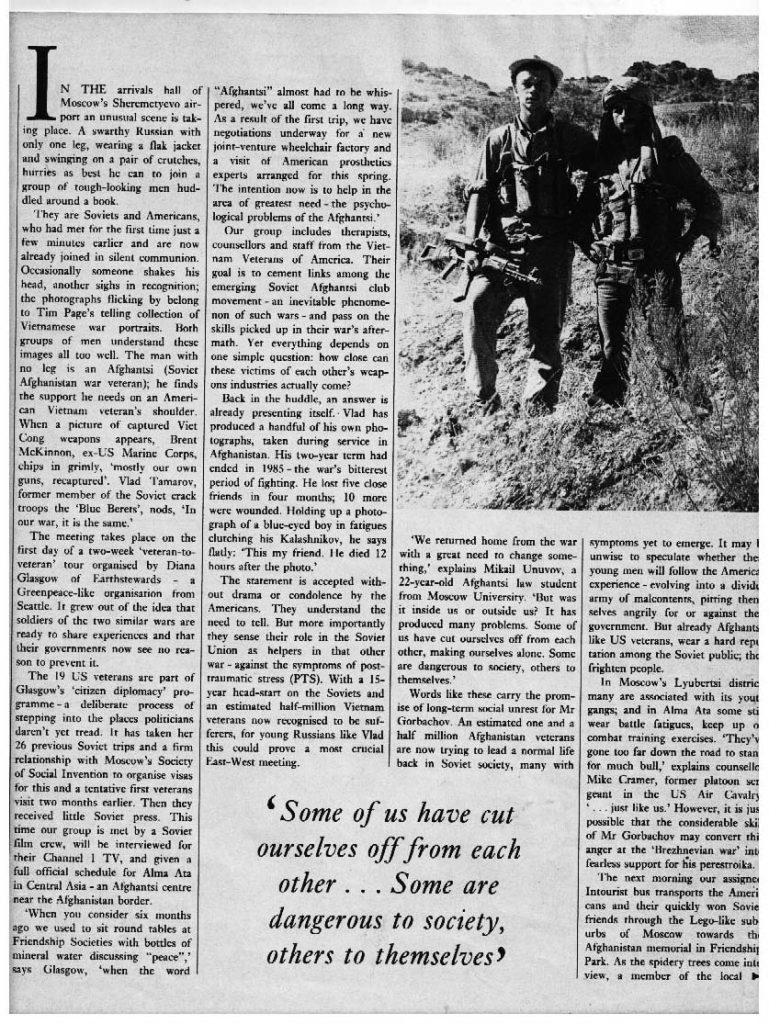

….men who’d eluded the Army for years. He knew he must act, not only to protect himself but also the public. His experience of urban combat had taught him what to do. Following the Yellow Card ‘Rules of Engagement’ as best he could he hurried home, found his Army fatigues, helmet and visor, took out his weapon – now a shot gun kept for rabbit shooting – and established a defensive ‘observation post’ in his flat opposite the vicarage.

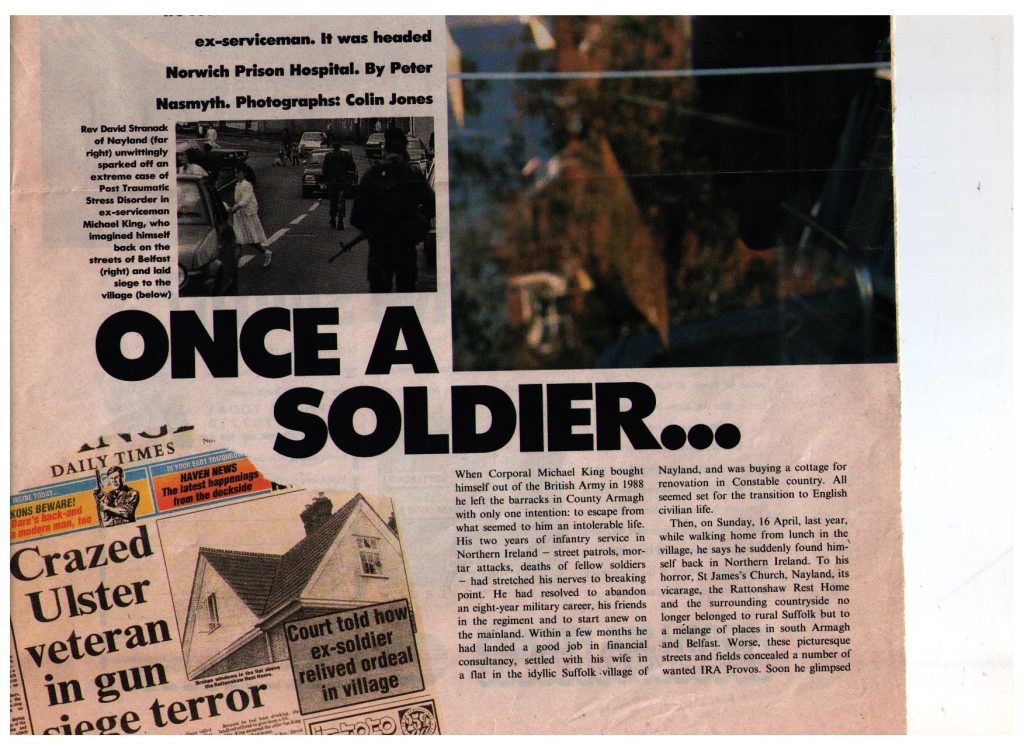

What followed was an event that baffled the inhabitants of Nayland. He proceeded to open fire on the empty fields and walls of the village around him. The first shots hit the vicarage, where the Reverend David Stranack had just finished mowing the lawn. The sound of breaking glass and sight of a lone gunman sent him quickly to the phone. When the first police squad car arrived King shouted at the officers to leave the area and keep civilians away. When they hesitated, he trained the rifle on them shouting they’d stepped inside a fire zone and had 10 seconds to leave before he recommenced shooting. They retreated and called in reinforcements, police snipers amongst them.

At that point nobody could be expected to understand that this man in the second floor window, wielding a gun had little in common with Michael Ryan, the Hungerford gunman. That the irrationality gripping his mind set out not to destroy the public but protect them; that the amiable Michael King chatting in the ‘White Hart’ some thirty minutes earlier no longer existed as a civilian in peaceful Suffolk, but as a Section Commander actively engaging the enemy in a West Belfast fire-fight.

The next 18 hours turned into a nightmare for the police and those close to King. His wife Beverley, had been confronted in the flat by a husband who failed to recognise her, who instructed her to lie face down on the couch as he fired precautionary shots through the ceiling (to kill any terrorists in the roof space). The police who, to their credit, held their fire, faced the task of talking this irrational, operational soldier into surrender. They’d guessed something of his confusion when he instructed the Police C/O over the car radio to position officers in key local positions – one being Divis Flats, in West Belfast.

As for Mike King himself the power of the emotion propelling the hallucination just wouldn’t release its grip (he claims he could actually see the ‘provos’ faces as ‘shadows’). He found himself drifting in and out of the fantasy, in fact a ‘flashback’ an extreme symptom of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

When I talked to him at his parent’s house after his release from Norwich Prison, where he was first kept before his trial, he described the experience; “When I saw the vicar there was this feeling of absolute revulsion, fear, terror; it was like being transported back nine months to Ireland. I thought I was in Armagh and I conducted an operation as if I was in Armagh… The problem was my having access to a firearm.

Everything that then happened made it go deeper. The sound of the rifle: talking to what I believed was my command station (on the police radio); talking to an opposite commander; the fact that it was rural (like South Armagh); all made it go deeper.”

In desperate attempts to halt it he began to hit his head with the rifle butt. Eventually when the symptoms did retreat, reality presented the full import of what he’d done. He found himself crouching inside a garage in a cordoned-off village, surrounded by armed police, knowing he’d just threatened his wife violently with a gun, (she spent three terrified hours locked in a cupboard). That his friends had watched him shoot at their homes, that the police carried a list of charges as long as his arm. But worst of all he could find no explanation for his loss of control. Knowing nothing of PTSD or its treatment he concluded himself as ‘beyond help,’ a danger to society and called on the police snipers to “take me out.” But the police had sensed the threat to the public had ceased, and the only life in grave danger was King’s – from his own hand.

Through the night two officers talked to him and finally convinced him into the option of surrender. Miraculously he had shot no one and in fact damaged only property.

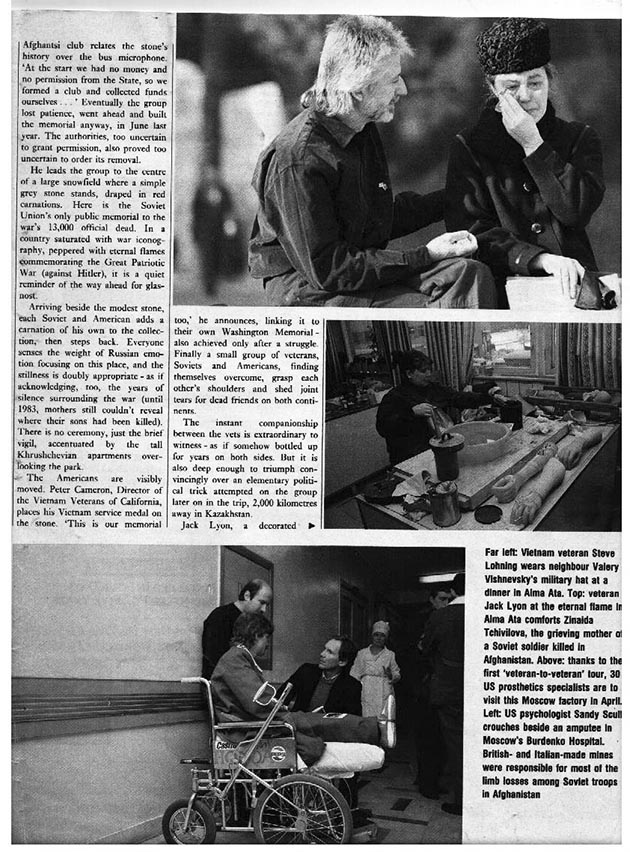

King spent two months in Norwich Prison. During the time he wrote letters to those he’d threatened expressing deep regrets. He received a surprising amount of sympathy in return. David Stranack whose house was most damaged showed particular understanding and certainly his and other’s support maintained King’s will to live inside prison. Although his symptoms amounted to text-book PTSD – as laid out

in the internationally accepted Diagnostic Statistics Manual lllR of the American Psychiatric Association, (DSM lllR) it took some time for word to filter through to the British Army and their expert on PTSD, Major Jeffrey McPherson then at the Queen Elizabeth Military Hospital at Woolwich. When McPherson finally diagnosed King with the treatable PTSD – a delayed stress reaction not a mental illness per se – he became eligible for bail, under strict conditions.

With events like Zeebrugge, Lockerbie, King’s Cross, stacking up around us the phrases ‘disaster psychiatry’ and ‘stress management,’ the concepts of re-emerging trauma and intrusive memories are graining credibility. The flashback is simply a particularly intrusive memory. Services like the Fire and Ambulance are recognising the long-term dangers of trauma to their officers and now encourage them to engage in trauma counselling after harrowing events. The problem begins when we turn to the profession most likely to encounter traumatising events and in the greatest numbers, the Army.

Our largest military service is painfully unprepared. As recently as 1985 the Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps published a paper attempting to deny any military linkage to PTSD symptoms in soldiers. This in spite of the many soldiers still suffering symptoms of ‘Shell Shock’ and ‘Combat Fatigue’ from the two World Wars, plus the on-going adjustment problems of Vietnam and Falklands veterans. Although today the Army will admit to combat related PTSD, it still provides only one clinic a week at Woolwich, its largest medical facility, and no information what-so-ever on these

symptoms for soldiers leaving the service.

Roderick Orner – now District Psychologist in Lincoln – believes this represents a cruel neglect. While working as a clinical psychologist in South Wales he encountered many PTSD problems among Falklands veterans in the Welsh Guards. When he appealed to

the Ministry of Defence for statistics, they admitted to an absence of studies, so he offered to conduct one. They agreed on conditions he take their comments into account before going to press or contacting the media. Finding this unacceptable he

declined their terms but continued to undertake the survey independently. His findings – about to be published – draw on 53 interviews with veterans. They indicate that 60% have at one point met the criteria of PTSD as laid out in DSM lllR. If this statistic is even partly indicative, one can draw distressing conclusions about the large population of ex-servicemen now re-integrated back into the population; and the

second hand pain passed on to their families. In 1988 Orner tried to organise Britain’s first PTSD conference, only to find it blacklisted by the MoD. Says Orner, himself an ex-serviceman, “the most interesting statistic of all is the absence of statistics. To me this indicates a disastrous failure of courage by the Ministry of Defence to match the

courage of their servicemen in the South Atlantic and Northern Ireland.”

Mike King says the failure has# developed a bitterness toward the institution to which he devoted his life from the age of 17. “What the Army needs to understand is we’re not just guys that turn into robots with uniforms on; we’re human too.” Which raises a disquieting question. Are the troubles of Northern Ireland restricted to the English mainland, simply as IRA bombings; or does another ‘hidden war’ wage within the emotional lives of many of its combatants – and their families – once they return home?

“Imagine walking down an ordinary British street full of people that hate you, many to the point of killing you; imagine then going into their homes and tearing them apart, not because you want to but because you have to, looking for weapons; imagine passing walls deliberately painted white by locals to give snipers a clearer sight on you; or being hit by a shit bomb (excrement inside a crisp packet), or wondering if this next street corner will be your last…”

Tim Lynch’s memories as a ‘squaddie’ in Northern Ireland still burn brightly; as they do from his time in the Falklands campaign. He’s never met Mike King, but feels he understands what he did. He also suffered PTSD symptoms; less severe, more common ones; the intrusive memories, recurring nightmares and sleep disorders, suppressed rage, waking up at night trying to attack his girl-friend, the desire to cut himself off from society.

He has now recovered, but the fireball rising above the Sir Galahad, and its horrific aftermath will always remain hard to talk about. When he does it emerges very slowly, word by word, the pauses are painfully eloquent “It was a very strange afternoon; carrying people who were dead; everyone else moving around; sooty; all very quiet; with the lingering smell of burnt flesh…”

Yet tied in with these images is the cult of Army machismo; that rough and ready peer pressure supressing admissions of sensitivity. Add to this the institution’s fear of psychological casualties in war (surprisingly high, at least 20% during the Normandy evacuations) with all its implications for promotion, one can see why so few soldiers want to come forward.

In 1984, just after the Harrod’s bombing, King had experienced another lesser episode of PTSD. It happened while on leave from his battalion’s intelligence section. He was arrested in an abandoned house which he deludedly believed the base of the

bombers. “It came from all the same symptoms, lack of sleep, isolation, and a sense of guilt at why should the English police, in the capital city of my country have to deal with a problem I should be dealing with as a member of the military. The civilian psychiatrist put it down to depression but told me to consult my battalion’s medical officer on return to base. When I told him the symptoms he said ‘yea, no problem, we’re being posted to Ireland, let’s just leave it there.’”

So instead of a medical discharge, King received a two year tour in Northern Ireland. Of the mental agony leading up to his second episode; “If there had been a place, a person, or even just a telephone line where I could have called during that time my life was ruled by PTSD symptoms, then all this probably would never have happened.”

Until last October Major Jeffrey McPherson’s post as Senior Lecturer in Psychiatry at Woolwich Military Hospital placed him close to the gods in Army psychiatry. He, along with Surgeon Commander O’Connell of the Navy, recognised the need for proper

provision and facilities for PTSD. In 1987 he formed the first PTSD group at Woolwich without any policy or direct financial support from the Army medical hierarchy. His intention was to establish the Army’s first clinic. (The Navy already operated one at the Haslar Naval Hospital, Portsmouth where by 1989 O’Connell had treated

over 500 cases). McPherson recalls; “It was really a one-man-and-a-dog affair, we received no encouragement, and had to fit it in where we could, which at its height amounted to half a day a week. However the few we were able to treat – about 70 in all – responded well; we had a high success rate in terms of getting rid of symptoms; but pretty poor as far as going back and serving. Most of the guys were discharging out of the service.”

He continued to press the Directorate for a proper PTSD programme, also to include educational and preventative services during training. “They gave it a lot of lip service but in the end simply posted me to Germany; which is the Army’s way of saying ‘give it up.’” Which is what he did. Both he and his most experienced Behavioural Therapist, John Rose, resigned from the Army in despair.

Dr. McPherson, who has dealt with dozens of PTS flashbacks. “The memories laid down in states of aroused trauma are very strong. They’re unforgettably encoded into the brain. Some veterans say ‘its like a film running in my head.’ When the memory is triggered – say by a car’s backfire – they experience an immediate physiological

response. The flashback comes when this shuts off the normal monitoring facilities. This can last from a few seconds to in some cases days.” On the flashback scale King’s experience ranks well below the worst. In 1974 a Vietnam veteran took joggers and

Park Rangers hostage in a Los Angeles park, believing them to be captured Viet Cong, for nearly a day. The rush hour freeways had to be closed and a Vietnam veteran Psychology Officer eventually flown in to impersonate his commanding officer, before he released them – still believing himself in Vietnam.

Such dramas inevitably led to headline coverage and a widespread public perception of the Vietnam Veteran as a ‘walking time-bomb.’ Quite unfair – since a good many veterans experienced little or no trauma. Both King and Lynch are concerned about such possible over-reactions here. Says Lynch, “I’m afraid of that American stigma where people assumed veterans were baby killers, drug addicts, psychotics, because then they stop treating you as human beings and put on the kid gloves.”

In America veterans organised independent organisations where PTS sufferers could

meet and talk, away from the anxious eyes of the Army. They formed ‘rap groups,’ that quickly centralised the healing process and saved many lives (they say as many veterans committed suicide after Vietnam as were killed by the Viet Cong). Today at least 70 ‘drop in’ Vet Centres are dotted all over the United States. In Britain young ex-servicemen seeking solace outside the Army for events they feel no civilian can understand, have nowhere to turn. Says Lynch, “Simply to be told if you joined the Army you knew the risks is not enough. To me that’s like saying if you boarded the ferry at Zeebrugge you knew the risks.”

Most PTSD sufferers experience lesser symptoms than King, but can still wreak havoc on wives and families. Furthermore some soldiers feel unable to confess to their part in undercover operations, or their mistakes. Lynch says, “What we desperately need is some kind of informal, non-rank orientated group, place or referral where soldiers and ex-soldiers can come and talk, tell their feelings off the record. Soldiers who are feeling something but don’t know what it is. We need to be able to put our experiences out, our anger and guilt, to people who’ve been through the same thing, who we know are on our side. Most civilian psychologists, while well meaning, haven’t got a clue what happened to us.”

On the 20th November 1989 he was committed for trial at Bury St Edmund’s Magistrates Court. He faced six charges, four for ‘Criminal Damage’ one ‘Possessing a Firearm with Intent to Endanger Life’ (carrying a life sentence), one of ‘Threatening to Kill a Police Officer’. He pleaded not guilty on all counts. Five months later he appeared before Ipswich Crown Court to change his plea to ‘guilty,’ to the Criminal Damage. He received a three year probation order contingent on his continuing therapy. The serious charges of ‘intent’ were simply left on file (the prosecution deciding not to press them).

For the first time in a British criminal court a defence of PTSD had been used, and successfully. Sentencing King, Justice John Turner said “I am now satisfied you were suffering from a serious condition of trauma associated with your service with Her

Majesty’s Army… and there is no real risk of a repeat providing you undertake therapy.”

King’s major fear – for his liberty – has now passed. What remains are scars of an event that never should have happened. Scars growing out of other events, the kind young

soldiers are experiencing today in Northern Ireland. King will never forget the death of his friend Tony Dacre, “…on 27th March 1985.” Five years on and his voice still trembles. He knows he bears no responsibility, that he could have done nothing, but

it makes little difference to this response of the then 21 year old. “He shouldn’t have died; and you carry that around for the rest of your life… I can’t stop myself feeling guilty. Its irrational guilt I know but it’s still guilt.”

One cannot help but think that some still carry more than their fair share

THE OBSERVER MAGAZINE Spring 1990